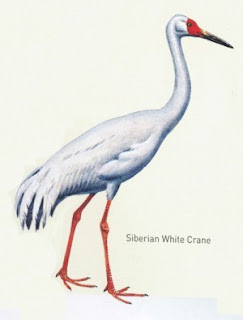

Siberian Crane

Class: Avia

Order: Gruiformes

Latin name: Grus leucogeranus

Range(s): Some birds breed on areas at Central Siberia, but main population nowadays exists on the Northeastern Siberia. [From the latter mentioned flock most winter at China near Yangtze (Lake Poyang). The birds from other populations migrate closer the Caspian Seas and the wintering areas are situated on Iran and India - But according the ICF-site main part of the stock migrating for Indian site were been on continuous decline over some past decades and may appear nowadays practically non-existant.]

IUCN Status: CR (Critically endangered)

/Cites: Appendix I / CMS1 : I , II

(about...2000s situation)

For the backgrounds. This chapter (on these series of the endangered) is devoted for cranes. As a group, the Gruiformes (or more particularly true cranes, Gruidae) are very especial birds, from both cultural or conservationist view-points. Their behavioral traits like courtship dancing and equally renown manner of birds flying on V-formation when migrating (when seen on the skies and in the past this was often associated for omens in the beliefs), as well their particular vocalizations, all have given grounds for various stories told by humans. Cranes (Gruidae) are present on most real continents, excluding only the South Americas(though, there's related species of birds).

From the taxonomic histories it's mentioned earlier been usual that various morphologically resembling wetland birds were placed for the Gruiformes, because of the difficulties classifying them for other groups (not necessarily all had much in common otherways). Whatever their exact relations to these 'more or less closely resembling species', the real cranes are usually seen consisting from about dozen+ species. By their evolutionary histories cranes are believed rather ancient among the birds. The subfamilies may possibly been already distinct around Late Eocene (some 30+ Million years ago). Current genera perhaps existed on around 20 Million year ago, and Johnsgard on his well-known 1980s book actually mentions that some unearthed crane fossils from the same Miocene periods have identical humeral structure with the modern Sandhill cranes (Grus canadiensis). He also mentions this possibly (maybe) is oldest known fossil evidence from any extant bird species.(Johnsgard 1983, 9-10) Current view, however, seems assuming that the extant species are somewhat younger by origin but still among the most ancient from avian lineages. Modern genetic research probably has also reached further detailed picture from that (Gruidae taxonomies) concerning relations of species. Without having viewed any of that, it seems also sometime been assumed Black- and Grey Crowned cranes most evolutionary archaic from cranes, and at least they're also separated to forming a subfamily of their own, Balearicae (B. pavonina/.regulorum).

From the modern historical developments it's noticeable that the cranes, along with other waterbirds, have suffered largely from increased human uses of their favored marsh- and wetlands habitat. Many species besides prefer areas with the minimum human impact, and in the past many also used to appear on much wider ranges than generally today. It is estimated that of larger species fx the Whooping Crane(Grus americanus, EN) may have numbered in thousands still at the mid of 19th century, but had become largely disappeared on most of its earlier range until early 1900s, and now it appears as one of the better known conservation examples of birds. Species slow recovery may have been taken the most of the 20th century.

Noteworthy cultural histories. From their many appearance on cultural beliefs and mythical stories (and the folklore fx), the cranes also belong for best known of the birds. There's cranes stories, especially inspired by their enthusiastic courtship dances, in the cultural heritage around various places in the world. And as well, crane dances performed by humans appear been practiced on such variety of cultures like the Ainu people at Japan, Oskits of Siberia, Australian aborigines, (ancient) Greeks, on Korea, fx.

As one of the best known antique tales Johnsgard mentions story from the death of the poet Ibicus (6th century BC), who was attacked by thief. He called for the passing cranes and these followed the attacker until he confessed the crime. But, certainly among the strangest of the antique tales (at least on the light of our generally very superficial view on any of these mythical histories and modern interpretations from those) seems to be a 'fable' from fights between the cranes and pygmies - from which following gives a short description:

“Aristotle, Homer and many other early authors believed that the cranes regularly engaged in warfare with Pygmies, or geranomachian. These Pygmies were believed to live in caves and were called Troglodytes, and at times were thought to ride on the backs of various animals. According to Pliny, the Pygmies were driven out of Geranea, their first city, by cranes, and later made warfare with them, attacking with iron weapons and darts or by riding on the backs of rams and holding in their hands a kind of clapper. They attacked the birds at the time of their breeding, descending thus on their nesting areas and destroying the birds and their eggs. This was done only during the breeding period, for later in the fall the arrival of other cranes might overthrow the Pygmies by their very numbers.” (Johnsgard 1983, 71-73)

Probably these stories appeared with different meaning and importance for the antique people than they today, maybe. But, quite powerful and mythical of it's contents story also remained in the folklore well for the middle-ages and probably later. Greek name for cranes, geranos (or gereunos) is said to probably originate of the above story. Another equally common and popular story is the one told from cranes carrying a swallowed touchstone - that was believed usable to test for gold, story foretold also by Aristotle (although he noticed it untruthful.)

Cranes, or actually observing them (from the antique authors observing cranes migration also is mentioned by fx Pliny, Plotinos, Plutarch), seems as well have contributed several alphabets for the Greek letters. Later, and on other languages, various terms may have had origins of similar kinds; Johnsgard mentions the old English term for family tree being pied de grue, referred as “crane's foot” - from which also the word pedigree. Origin for word cranberry isn't too difficult to guess, particularly as the cranes do feed on those berries. And, Latin word congruere means agreement (perhaps derived from belief about cranes social behaviors and practices). Name of our exemplary species at this, Siberian crane ie Leucogeranus, appears consisting from leukon (white) and geranos (crane). (Johnsgard 1983, 70; 239)

As well mentioned, that probably the cranes also have historically been domesticated on some places (or bred at captivity for foods and perhaps to other purposes), at least occasionally in the pasts. At least such has been concluded fx from some ancient Egyptian tomb paintings but also this is known been practiced on some other cultures in the historical times2. So, apparently the cranes have some time past presented even more important cultural role and maybe appeared more regularly in the 'context of the daily life' (for some level).

Migrations. Nowadays and as well in the past, no doubt, most usual sight of the cranes is when their seen on their spectacular migration flights. However, migrating appears one of the most universal practices for variety of birds; The instinct for this on birds may have evolved as the result of millions years evolutionary developments (and fx, individuals usually inherit certain annual rhythm which permits them being ready at the right time of year.) The genetic basis of migration also lead birds preferring formerly learned wintering areas. The behavioral practices may change according fx climatic changes but do so only gradually; They are somewhat 'encoded' in the birds genetics. Learning by following also plays part and the younger birds usually do adopt a more specific manner of choosing for (wintering) sites after their parental birds. (Elphick 2007, 28-9) With similar combinations of learned skills, compassing with the aid of light and 'genetic instinct' the birds are also capable finding their homing areas from behind vast distances. They have excellent senses of directions - sometimes specimen released from the different sides of large Oceans have been found back on their homing nest after a few days. A characteristical feature formerly commonly used in the sending of the carrier pigeons, probably.

The different species and different populations prefer/are adapted for varying routes, but mostly the direction is from the colder regions towards southern wintering sites where more food will be available on winter months. Many do travel thousands kilometers, and migration also often appears difficult and risky journey (fx from some smaller birds large percentages of individuals fall victims for natural predators, and as well migrating appears additional stress for their physical strengths. Therefore preceding the migration journey most birds also do gather extra reserves to be better prepared for period of that exhaustive flight.) Often survival on journey depends also on correct timing and finding of suitable staging posts on the journey.

Terrain affects too, the mountains form physical barriers that need to be circumvented or crossed, and similarly the desert which appear inhospitable for most species. (Yet, it's said that some species travel for mountain areas which they find resembling their summer nesting areas.) Normally the wintering region for birds are around lakes, river deltas or other wetlands, which provide readily available food sources. That so, because migrants are more likely to lose in competition from food on areas where there's more specialized resident species, like in the forests. (Though, it being not universally so.) Also, typically migrating species can travel by different routes when returning, from reason that weather often also differs on different season.

By origin, from the distant pasts most influential thing affecting the development of migrations appears been continuous change on the ranges of ice sheets; from the last two million years about six cold periods are known, last two from during the previous 150 000 years. As result, if viewed on longer perspective, the ranges of suitable habitat for single species may have changed repeatedly (concerning both summer and wintering areas). Another factor concerning the birds genetic adaptations and behavioral practices at the migration - and at least as much influential for the development of these - has been the drifting of continents, from during some tens of millions years. About 50 million years ago there were birds that would be identifiable to the ones that exists today, at least on the group level. At the time Africa fx was close the Eurasia by long distances of coast like it is today, but Indian continental plate fx was separated from the Asia about some couple thousand kilometers far. As assumed, resulting from that the most complex migration systems are evolved between Eurasia and Africa.(Elphick 2007, 8-9; 82-83)

In addition to other learned practices usually birds prefer selecting the easiest route, but naturally the shortest passage is not always fastest - because there may barriers fx in form of the seas, inhospitable grounds (like deserts or mountain ranges), etc. So this also depends on the evolved patterns, more precisely requirements and capabilities of the particular species. Wind is very important factor, so fx larger birds take use of the higher winds that are stronger than closer the ground (ca over 500 meters). The book mentions of the observed cranes migration heights an example from the Common cranes (Grus grus); Birds were observed when departed of the Swedish coast and crossing over Baltic Sea at about some 500-2000 meters height - generally relatively 'low' if compared some following examples. From other crane species, Demoiselle cranes (Anthr. virgo), that migrate past Himalayan must fly at least (over) about 4000 meters to cross the lowest passes. Occasionally birds apparently fly much higher, with aim to reach suitable winds fx. (From some of the better known larger migrating birds it is known fx that the Bar-headed gooses (Anser Indicus, LC) cross the Himalayan mountain peaks at 9000 meters height and Whooper swans (Cygnus cygnus), flying from Iceland to west Europe have been observed at the heights over 8000 meters). (Elphick 2007, 23; 97)

To take most benefit of the preferable winds, birds can also use some techniques for saving their strengths when on migration flight (as well as elsewhere when flying). Species with suitable broad wings and separated primary feathers are best capable to control directions effectively (birds of prey, cranes, storks mentioned as examples from such) and so they use Thermal Soaring – But the Slope soaring, however, means slightly different thing, although it also appears used by larger birds. The thermals emerge when the air over open spaces (also over roads, fx) warms up locally from the ground that is heated by morning sun. As result the warm air sucks more air and such raising 'air bubbles' permit the birds to gain height with spiraling flight. When having reached enough height birds (or fx in cases of cranes the whole flock one by one) may start a glide towards the next thermal. Technique also maximizes the most effective use of the winds when on travel. For the larger birds using thermal soaring is preferable since their sizes also means greater loss of energy in the regular flight of the same distances.

It can be effective also when crossing the oceans since thermal takes place also over the watery areas. However, usually the larger birds tend to avoid long sea crossing when possible, mainly from the reason that they can't raise for needed heights by muscle powers alone. On bad weather they would (probably) also more easily be in trouble there.

By thermal soaring the birds regularly are able gain some (fx) 500 meters height, which then can be converted for distance with gliding. Larger birds can also 'lock' their wings for preferred positions to take benefit from straight gliding away at the height of the thermal, losing height in straight line until having reached the next thermal to repeat process. This may appear a little slower way to travel than normal 'flapping flight' (of the observed Common Cranes, the book mentions reaching average about 60 km/h with regular flight compared to ca 50 km/h when soaring). But it saves the strengths of the bird and permits more energy-effective flight – and as well makes possible crossing longer distances within the same used travel time. (Elphick 2007, p 16-17,; 96-97) As the larger species generally are probably slower fliers than the small ones this perhaps gives them considerably help needed to crossing the (migration) distances.

Wetlands loss. Generally many larger high flying birds are perhaps relative safe on their migration routes, if compared to some of the smaller ones. However, all the distance is not passed flying on such heights and there's differences fx on preferred routes and other factors between species. There can also be other threats on their journey than predation by other animals or humans (fx, of the Whooping cranes, the most usual cause of injuring is mentioned being flying for power lines). Birds closely adapted to waters also need suitable wetland areas; some species may be adaptive for human created, artificial lakes (fx), some other less so. Cranes, obviously appear most dependable on natural areas on their historical wintering/breeding areas. From the North American species (Whooping crane and the Sandhill cranes) both appear birds of the open, grassy wetlands. Their populations are believed been fragmented originally, but as result the modern developments appear even more so. Both species do also have populations that migrate several thousand kilometers. (Elphick 2007, 58-59)

More generally, and on various parts of the world the wetlands have all the way become scarcer within the process of modernization. Typically most important characteristics for birds on the wetlands are often most inconvenient from the humans usual point-of-views;

“Seasonal waters with large areas of marsh are often vital for birds. Yet, in the tropics these areas may be turned over to rice paddies; in temperate regions, they might be ponded and banked to concentrate the water into smaller tracts for fish farming, for example, with the reclaimed area turned over to agriculture.

Estuaries have been used for centuries for trade and industry. It's difficult to think of the Hudson River in New York or the port at Rotterdam as important places for shorebirds, but they once were. Not only are the physical characteristics of such sites – the buildings, wharves and docks – unsuitable for birds; industrial effluent may also render the estuary sterile. Ongoing estuary development means the loss of staging posts and wintering grounds. Land-reclamation schemes, by contrast, can encourage birds. The polders in the Netherlands, for example, have provided marvelous habitats for a wide variety of water birds in the sump areas that are not destined for agricultural use.“ (Atlas of Bird Migration, 2007; p46)

Even if all the resulted modern developments wouldn't appear just that straightforward loss of habitats for the birds, fx the cranes typically suffer from the alterations on their preferred watery areas. Various factors can affect such habitats for the worse (if not directly destroying them by changing areas for the agricultural purposes, fx). Such things that can alter their usability for birds are (fx) construction and the use of waterways (erodes wetland zones), pollution, barge traffic (carries fx various contaminants and petrochemical products capable spoil waters), oil extraction near birds nesting areas, agricultural expansion, reed harvesting, river channelization, side-effects of the deforestation, urban expansion, general wetlands drainage, other water development projects (like dams), water shortages, etc. (Combined from the ICF-site pages information on cranes, 2009). Any single factor probably fx can have harmful impacts on the birds breeding, ao, and also usual, the increase in continuous human activitity (generally, even without any particular disturbance) can have disadvantageous effects on that.

Rails, ao are some birds usually mentioned to have suffered of long-term habitat loss. And various other water birds. Similarly many shorebirds are most dependable on those declined wetland environments. One (of the European) shorebird species often mentioned as example, or particularly vulnerable, is been the Slender-billed Curlew (Numenis tenuirostris, CR). It is (/or at least recently was) considered close total disappearance, as there had been reduction in their main range during last 100 years and in the more recent decades more drastic reduction, too. Major stressing factors for most shorebirds are the changes in agricultural practices, drainage of their watery environments and numerous grasslands been turned to crops production (the natural grasslands appear rich sources of food for birds with 'full meals' of insects available, etc). But, similarly patches of standing water and shallow waters that appear preferable to birds are less usable for humans and so may be turned to land in agricultural use. Also pasturing animals wandering for open fields and low waters easily disturbs birds on their important nesting areas.

To the contrary, fx in cases of some ducks the increase of artificial waters during the same periods of time (100 years) may have provided suitable new environments. Somewhat resembling case perhaps, fx the Swans, from which some species earlier also were hunted to low numbers in Europe, may have recovered from partly similar reasons - and during some last 50 years 'til the present days even have spread for the new lakes and ranges from the places where they were been brought by humans(like urban areas, cities parks, etc).

From the diving ducks Pochards (Aythya ferina) are mentioned to benefit from human created reservoirs, gravel pits and ponds which offer ideal conditions for searching their foods underwaters. They are still largely dependable on seasonal conditions. Various (migrating) ducks (Eurasian teals, Anas crecca, fx mentioned as example) move gradually for their wintering places on southern Europe when the cold season arrives. When returning from the migration, and if waters still appear freezed or marshes dry because of the weather conditions, the ducks don't find enough food so they move for adjacent areas in search of more favorable feeding areas. If the ducks arrive (for their usual ranges at western Russia) at the time of spring droughts they are also forced to move on searching more suitable areas, even outside their usual breeding ranges. Similarly droughts on late summer at their breeding areas may push birds for migration on earlier timing. (Elphick 2007, 84-87) More particularly the ducks appear (differing from most other birds) also more easily cross-breeding with resembling species. Of the endangered ducks, the White headed duck (EN) appears mentioned an example of species that has suffered from drainage of it's breeding areas (around 50 per cent loss in 20th century, mainly on the eastern European area). The decline of habitat and resulted patched distribution also makes them vulnerable for the genetic loss since the birds easily bred with other duck species, particularly with Ruddy ducks that have escaped for the wild (from their originally farmed populations) (McGavin, 2006).

In overall, however, the ducks (Anseriformes) perhaps aren't too much resembling cranes of their characteristics and behaviors. Since the latter mentioned appears the main genera presented on this, we can move on to them.

The endangered Cranes / Siberian crane. From past conservation history some of the better known crane species are the Whooping crane and Japonese crane (Grus Japonese, EN). Nowadays most threatened apparently is the Siberian Crane, so not surprisingly it's also been on the conservation focus at recent decades. By population it is mentioned still (as we notice that) appearing more numerous than formerly mentioned, but because of more continuous decline is listed critically endangered and contrary to preceding examples also still was (at least rather recently).

Of the endangered cranes, the Whooping crane is a species which already before the modern (19th century) decline may have appeared on somewhat reduced area from the originally much wider geographic range. Of course, would be rather misleading consider it been on the way out or having presented relic of the past times – like usually the case on such definition from most animal species. It's mentioned having had a scattered but widely distributed populations across Northern Americas. The main decline of the species on second half of 19th century is lot researched and has been noticed largely have resulted from the birds main habitat areas been converted for agricultural lands (that generally timed for period of the westward expansion by the settlers). The decline had it's reasons from the unregulated hunting, as well. (ICF-site, Whooping crane, 2009).

Lot resembling the above example appears also historical endangerment of the Japonese crane; On the feudal periods it was held on appreciated status (fx, hunting of species is sometimes mentioned been permitted only for the emperor). Later fx hunting of birds become more common and it's populations went for decline. Also Japonese crane once appeared on wider ranges, it fx nested on both of the northern islands of Japan (Honshu, and Hokkaido, marsh-lands on latter nowadays forming the current habitat area), and as well may have wintered on the central Japan. However, it also declined/become threatened during the 19th century. On the beginnings of the 20th century amount of the birds was at very low, only about 20, from which level it recovered only slowly until 1950s. Since that the population is noticeably been seen on general increase. (Johnsgard 1983, 63; 199) Japanese cranes however , also appear by different population on the east Asian continental range, which equally has fluctuated but nowadays still is found numbering somewhat more numerous, over 1000 birds still recently at least (apparently the often used name Manchurian crane originated of these populations). The Japonese population isn't migratory, at least outside the Japan islands, but the mainland birds appear migratory. (ICF-site, Japonese Crane 2009). In case of the both aforementioned (Whooping / Japonese cranes) the recovery of birds appears been a slow increase from populations that were on the nearly extinct level at the turn of 20th century,

The whooping cranes protection efforts may have begun the earliest, so much of the knowledge from cranes is based on that. At the both cases the conservation has contained/been focused on protection of birds crucial wetlands and the international co-operation on improved conservation at these areas (Japonese/Manchurian cranes main populations fx appear on large wetlands mainly situated at the northeastern China - same areas that the Siberian cranes largely use on their migration stopover sites as well - but also on fx on Russia. The birds wintering areas are on Japan, China and Korean Peninsula). (ICF-site, Japonese Crane 2009)

--

Also the Siberian cranes (Like the Japonese/Whooping crane) are primarily white from plumage. They appear slightly smaller by size and prefer highly specialized wetland habitat (actually mentioned are as the most aquatic of cranes). Birds nest in bogs, marshes, other wetland types of the lowland tundra, also on the transition zones of taiga/tundra, preferring wide expanses of shallow fresh water areas. Their main breeding ground consists from large range on the northeastern Siberia, non-breeding individuals occasionally observed on more southern regions

From the Sandhill cranes it seem noted (by Johnsgard) that cranes tend to be 'fundamentally highly dispersed and territorial on their breeding season' - They prefer large territories, and a typical average territorial range for a pair can be closer 25 hectares (Yet, on areas of different environment it may sometimes consists of only few hectares). Territorial range of the Siberian species seems mentioned similar by size. Cranes generally lay a clutch of about 1-2 eggs (all species except Wattled crane and the crowned cranes). Siberian cranes nest typically is built on tidal flat, or in flat swampy, grassy depressions. Unrestricted visibility to the surroundings apparently is of importance when birds select the nesting sites. (Johnsgard 1983, 45 ; 134) As large birds they are somewhat capable defending nest from smaller predators but there's species that typically prey on the eggs or that can otherways destroy the nest; fx, the latter includes dogs accompanying reindeer herds, former at least the gulls and jaegers (Johnsgard 1983, 139). From diet the Siberian cranes are mentioned primarily vegetarian outside the breeding season, food consisting of fx roots and tubers from wetlands. At spring on breeding grounds they may, like also typical for the cranes, eat fx berries, rodents, fish, insects. Siberian cranes also engage in unison calling and the usual cranes courtship 'dancing', like most species. The Siberian cranes are known to have the longest migrations route of cranes, the travel distance may extend 5000 km.

Along with the other species historical decline of Siberian cranes was largely resulting from the human influence, to the level that Johnsgard describes also it having gone through 'catastrophic reduction' by numbers during past 100 to 150 years. The major causes known contain effects from the human encroachment on its Siberian breeding area, increased (illegal) hunting as result, and mortality also on migrations. It probably also wintered on various other areas at the past. Formerly it is known having wintered on number of areas at the Iran, as well in Japan. Bird probably also nested on areas more far in the south than it currently does, and it was still abundant in the forest-steppe areas of western Siberia on the 19th century. Later, it started to become scarcer around the beginnings of 20th century. Changes of the preceding century, mainly drainage and agricultural development include in the main reasons of its reduction on that range. (Johnsgard 1983, 60-1 ; 133-4)

Nowadays, for some time the birds breeding grounds on Siberia have been protected, and probably appears the case also elsewhere on it's known area of appearance. From current population count birds Fact sheet viewed gives us an estimate from about 3200 birds (of which 95 per cent are said belong to the eastern population wintering around Lake Poyang, China.) (BirdLife International, Grus Leucogeranus [IUCN] Factsheet 2009). - However, Johnsgards listings of the endangered cranes gives significantly lower estimates from the number of extant birds (at the largest flock). So on the basis of this information available to us (which is mostly from the net), it seems that; Either there's fault on some of these numbers /Or since that [1980s] there's been massive increase of birds and possibly later found breeding areas of them ; though that seems not very likely and the bird actually is mentioned been on decline / Some other reason causing this contradiction at the information.) Although, it can be said that fx the estimates from the birds counted on their wintering areas at different years are mentioned somewhat vary as the non-breeders don't necessary migrate for the same areas yearly. As well, since the books rather old – usually referred as the 'Cranes bible', though – it can be said that there's probably some 'gap' in the information we've combined from various sources, and they appear represent knowledge from times separated by some decades.

Main reasons for the birds decline on preceding century/(-ies) or, the human brought pressures on them most usually mentioned are the agricultural development and hydrological projects (latter mentioned nowadays mostly concerns the eastern main flock on its wintering areas). In general the lists of things that can have negative effects includes industrial pollution, hunting along the migration route, sports hunting (of other birds, popular on some stopover sites), fishing activities, other urban development, seismic testing for oil, oil exploration, water development projects (can change hydrology of the flood plan wetlands), built water channels on those areas, ao. Also, from potential threats mentioned are changes on lakes/sea water levels, climate change effects (like the possibility of prolonged droughts), avian influenza, etc. In during past decades western populations of the Siberian cranes mostly has suffered from hunting and mortality along migration routes for wintering areas at the Caspian coastline (on Iran) and India. Bird counts on wintering area on Keoladeo national park (on India) during the decades seem showing the general steady decline from amount of 80 birds at 1960s. (That having reduced for practically none on the more recent times and, as result flock(s) practically having become extirpated).

Been on the focus of a number conservation efforts since 1970s the Siberian cranes are included on many projects ICF has for the cranes protection; fx captivity raising centers for the species were been started already at the late 1970s. Also, it's mentioned as the main species in the SCWP (Siberian Crane Wetland Project) which targets increasing the ecological integrity network of the Asian wetland areas (protecting eco-regions of critical importance to migratory waterbirds). So the bird has some time also 'enjoyed' a status as the key species on the preservation of those areas. There's also (ao) mentioned an UNEP program supported grant addressed to protection of the main wetlands used by Siberian cranes.

However, as the migration route of the western population appears been/earlier passed through some rather unstable areas and countries, it's mentioned that more recently there's been efforts to establish them for safer migration routes/areas. Projects targeting for this have included fx the Siberian cranes eggs placed to be hatched on Eurasian cranes nests, and also the human 'guided' migration, where juvenile cranes on first migrations are been trained to follow the ultra-light aircraft (piloted by crane costumed human) – technique which is known have proven successful results on Whooping cranes and Sandhill cranes conservation. Protection of the stopover sites along on their migration routes is also mentioned (difficult in its entity and not quite possible throughtout the route, though). (Information of the above paragraphs combined from ICF-sites species page and the SCFC-pages – Which also gives more complete information from each of the Siberian Cranes flocks, their main threats and conservation efforts in general, see from the sources.) (From the basis of viewed information it seems that the eastern flock would practically remain as the only viable population left, unless other flocks of birds could have been established on more safer migration routes. But - of course - most in the precedingly presented only gives very brief overall remarks from any of these species and their protection.)

Consequently. The cranes are, perhaps, among better known of the conservation dependent birds. The International Crane Foundation was founded around 1970s already and there's actually a lot information from these birds and their protection been gathered. In spite of the very low points on population levels of some species, they've probably been more on the focus of conservation efforts than some other wetland birds, more recently noticed having declined. But, many cranes too still remain particularly vulnerable for effects of the modernization development and actually the recovery of these case examples mentioned may have been taking (the whole of) the past century. Nowadays, possibly their survival is on somewhat more secure levels. Also the protection on most watery areas probably appears better maintained (or at least official protection is more commonly held).

The wetlands generally been converted to agricultural areas and other human uses may have resulted also for increased pressure on waters in form of the pesticide chemicals, fertilizers and so on. These have effects on changing ecology of waters on these areas as well as do the built water power, fx. There may be effects of the erosion as well. Of course large number of natural and human modified wetlands around the world exist and many are famous of providing marvelous habitats to various species (of birds, ao). Like many river deltas and bird lakes. Even among lakes and areas that have been largely taken for human uses, some offer suitable areas and sometimes also the degrated environments have been returned for their former natural conditions.

But conclusively, in the long-term development it's still very obviously been reduction in the such habitats. Whether that may remain so in the future seems more probable because one cannot except fx the agricultural production needs to lessen. However, much also depends on the preferences, what is thought to be of importance and valued. Usually the protection of largely vulnerable species can be effectively integrated with efforts that benefit the eco-system in overall, most probably.

To someone who doesn't particularly see any temptation on getting one's feet cold and waiting hours fx at the peak of watch-tower, observing the birds may have always felt a little bit odd and uncomfortable hobby. But on writing these chapters I've actually become noticing that the emerge of the bird-watching (as hobby) may also represent important changes in the human behaviors and practices. And birds indeed have many exciting characteristics to learn about and some are pretty common even on suburban areas, if ones interested to observing them. (It can then also of course be said that on many popular wetlands renown of various birds as well there's also regular hunting of birds for foods. Appears rather different thing from hunting for sports, but nevertheless it also can nowadays form a major threat (like in case of some of above mentioned species examples). But times change and at modern world many changes also often take place lot faster than in the pasts – whether that will be for the better depends from various things, of course. More generally, the wild populations (of birds fx) are also threatened by accumulation of man-made pollutants and their effects, probably also appears an increasing threat, and can emerge as a more long-term factor too.

--

But, as we've now reached chapter this far, I guess it's better finish these series. At the beginnings it was to contain as well examples of endangered fish, insects also, but I suppose that would need a further more specialized observations, likely not much possible on these limits.

However, we may perhaps later add some example/examples from the seas/terrestrial endangered animals, if that would appear appropriate and purposeful. On the basis of these preceding chapters, most likely, the following sequels would then have to be selected on geographical basis - As the most other continents were presented at earlier chapters, additional examples would be selected of African and polar region(s), ie Antarctic, perhaps also Arctic (or, the Subarctic/Northern continents). But not necessarily on any closer days, anyway. However, with the unavoidable probability, we may write some more general chapter from aspects presented on this serie and maybe it should contain some (brief) historical perspectives, too.

--

Notes:

1. CMS = Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species (also known as the Bonn Convention), is an intergovernmental treaty on conserving terrestrial, marine and avian migratory species throughout their range. App I in this means migratory species threatened with the extinction ; and, App II migratory species that need or would significantly benefit from the International co-operation (at their conservation).

(From the other treaties conserning cranes / migrants; MoU refers for the species specific Memorandum of Understanding, created to help certain species conservation efforts. AEWA 'translates' as the Agreement on the Conservation of African-Eurasian migratory waterbirds ; If wish, check of those treaties/agreements more precisely from other sources...)

2. Captived cranes are mentioned depicted on the walls of the Temple of Deir-el-Barari at the Nile Valley. In the ancient Greece cranes were also tamed, and it's said that presumably the Eurasian cranes were the species been kept for domesticated uses. Similarly, also in Japan and kept by the Chinese royalty from at least as early as (about) some 2000 years ago cranes were maintained / kept domesticated by humans. (Johnsgard 1983, 51)

--

Sources:

BirdLife International 2009. Grus Leucogeranus. IUCN Factsheet. www.iucnredlist.org Downloaded on 18 February 2010.

Elphick, J. (ed.), (2007), Atlas of Bird Migration. Natural History Museum, London.

International Crane foundation (ICF) ;

(Pages on the Siberian Crane, Whooping Crane, Red-Crowned [Japonese/Manchurian] Crane.)

Siberian Crane Flyaway - Coordination site (SCFC) ;

(Has information from the Western, Central and Eastern flocks.)

Johnsgard, P., (1983), Cranes of the World. (Electronic version 2008.) (Available with Digital Commons license, on pages of the University of Nebraska. (http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/bioscicranes/)

McGavin, G., (2006), Endangered – Wildlife on the brink of extinction.

[Pics; from Elphick (ed.)]

-------

----------

Powered by ScribeFire.

![[Fig 2.; p.9]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhsCfSH7164PD5KvWgwkBKENMVO1Mo63i4knFFkOK4OeQMeU6eNM382G6SLJn1ZJHQMOtAFZj7qeGAZae55ir9JOMUUZD9KwTbl38AGpKntRNZY9isTfOZyfqaBXidaL1E8b73-vusuNcA/s1600/wegfkafoocao.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment